Patrick Nagano: a distinguished life beyond World War II internment

Return to QR Index

By DAN KRIEGER

Special to The Tribune

A crate of oranges landed Patrick Nagano in San Luis Obispo's very primitive jail.

Patrick was one of the sons born to Yoshio and Kanaru Nagano at the family home on Little Morro Creek in November 1918. He graduated from San Luis Senior High in 1936. That fall, he entered Stanford University where he made history by being the first Japanese-American to letter in a major sport playing varsity baseball. He graduated in 1940 cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, a strong wave of nativist fear infected the West Coast. The Nagano family understood the consequences. They leased land near Reedley and prepared to leave their Morro Bay farm. Patrick remained behind to wrap matters up.

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the military to designate "military areas" as "exclusion zones, " from which "any or all persons may be excluded." It was primarily aimed at relocating enemy aliens and all Japanese Americans, including U.S. citizens like Patrick Nagano.

It took less than a week before the military began removing all Japanese-Americans and Japanese from the West Coast.

Patrick Nagano recalled:

"A curfew had been imposed . . . We were confined to an area five miles in radius. At night we had to be in our homes by eight o'clock. As the evacuation date neared (there) were a few last minute details like paying final bills and closing bank accounts. This meant having to go to San Luis Obispo."

San Luis Obispo was nearly 10 miles beyond the limit. You had to travel nearly 50 miles to Santa Maria to get a permit from the WCCA (Wartime Civilian Control Authority) or travel 15 miles to San Luis Obispo. And so Patrick decided to take what he thought was a perfectly appropriate risk.

"Just the day before, a notice had come from the express office that a box of oranges from Reedley had arrived. Great! I could pick them up at the time. So off I went.

"One last thing to do was picking up the oranges. I was about to head for the depot when I ran into Bill Kuroda. Bill and I had been classmates at San Luis High School. Ever since the curfew, I had not seen or talked to any friends. I persuaded Bill to park his car and get in mine (and) have lunch together. I picked up the oranges."

When they left the depot, a San Luis Obispo policeman insisted they follow him to the police station and after hours of waiting, to County Jail.

"At the time, the jail was in temporary quarters squeezed into the old records building on the corner of Palm and Osos, while the new courthouse was under construction. The cell was small, dingy, ill-lit, and smelly. On entering the cell, I nearly kicked over a can brimming with the urine of former occupants."

The next day, Saturday, they were taken before U.S. Commissioner Richard Harris who asked Nagano and Kuroda, "How do you plead . . . Guilty or not guilty?" Both replied, "Not guilty!"

Harris advised them to plead guilty and imposed bail of $1,000, a huge amount at the time. Nagano contacted Pete Bachino, an insurance broker who was a stalwart friend of the Japanese. The banks were closed on Saturday afternoon, but Bachino finally made arrangements for Charles Serrano, a friend of the Nagano family, to post bail.

Patrick Nagano joined his family in Reedley, only to be moved to the Poston Relocation Center on the Colorado River Indian Reservation the following summer.

He volunteered for Army Military Intelligence Service and attended the Army language schools at Camp Savage and Fort Snelling, Minn. There he met and married Ann Ono. Karen, their first child was born at Fort Snelling Hospital.

The M.I.S. assigned Nagano to the European theater. His assignment was to be parachuted into the Japanese Embassy in Berlin before the Russians could obtain the intelligence documents. Fortunately for Nagano but not for the Western Allies, Berlin fell to the Red Army before that could happen.

Nagano returned to Morro Bay to become one of its leading citizens. He died last week at the age of 96. He was a prime example of what NBC anchor Tom Brokaw referred to as "The Greatest Generation."

Dan Krieger's column is special to The Tribune. He is a professor emeritus of history at Cal Poly and past president of the California Mission Studies Association.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/news/local/news-columns-blogs/times-past/article44893521.html#storylink=cpy

The Pat Nagano Story - Japanese Relocation and Evacuation on the Central Coast in 1942

Written by Pat Nagano

December 7th, 1941, and the events that followed had abruptly disrupted the heretofore tranquil existence of the Nagano family, who had been farming in Morro Bay since 1917

Our country had been taken completely unprepared by the bombing of Pearl Harbor. In the early stages of the war things had not gone well for our side. Locally there had been a shelling of our coast by an enemy submarine near Santa Barbara and the sinking of a tanker near Cambria. The possibility of the enemy landing on our coast was very real

These circumstances, fueled by outcries of anti-Japanese sentiments, particularly by those who had most to gain from our removal, made inevitable the ultimate evacuation of all Japanese from the west coast. This would soon become fact in the spring of 1942, when commander of West Coast Defense, General DeWitt, carried out Executive Order No. 9066, which gave the Secretary of War the authority to designate military areas and exclude all or any people from them. Despite the injustice, disruption, and hardship the order would impose on the Japanese families, it came as no surprise to me.

Areas most sensitive to the military, such as Terminal Island near Los Angeles, were the first to be affected. Families in those areas were given scant ten days to ready themselves for evacuation, forcing many to sell their household goods off the street for whatever they could get. Of all evacuees these people suffered the greatest economic losses and the most anguish.

Highway 1 served as demarcation, with those living to the west of the highway evicted before those to the east. Thus, our cousins, in Los Osos, the Etos, found themselves having to leave a month or more before the Naganos, who were actually closer to the Pacific Ocean.

The Etos and the Naganos chose to take advantage of a provision in the Evacuation Order that allowed voluntary movement to a "free" zone. Anyhere east of Highway 99 was designated "free." Etos moved to Ducor near Visalia: the Naganos to Reedley. There they hoped to sit out the war.

The Nagano family, by then reduced to mother, Nellie, and George, moved into a house on D Street in Reedley, which had been rented months earlier in anticipation of events. Ellen, the older of two sisters, was married to a flower flower and living in Mountain View. William, the eldest, had been drafted in February, 1941, and was stationed at Fort Ord. Dad had been interned and was in Bismarck, NorthDakota.

I remained behind. Arrangements for someone to look after our property needed to be completed. Then, too, it seemed our country's interest would be best served by harvesting as much of the existing crops as possible.

Little did I anticipate the events that would follow. Curfew had been imposed curtailing our movement. We were confined to an area five miles in radius: at night we had to be in our homes by eight o'clock. In spite of these inconveniences I managed to cope with the solitary existence. As the evacuation date neared all arrangements were in place. What remained were a few last minute details: paying final fills, closing bank accounts. This meant having to go to San Luis Obispo.

Just the day before a notice had come from the express office that a box of oranges from Reedley had arrived. Great! I could pick them up at the same time I conclude my business in San Luis. So off I went.

Everything went well without any unpleasant incident. In fact, everyone was genuinely sorry about the situation. With all the casualness I could muster I left everyone with, "I'll be back... as soon as we win the war!"

On last thing to do, pick up the oranges. I was about to head for the depot when I ran into Bill Kuroda. He lived in Shell Beach. His and my folks were from the same area in Japan and had all come to America about the same time. Moreover, Bill and I had been classmates at San Luis High School, and had graduated together

Ever since the curfew, I had not seen or talked to any friends. I persuaded Bill to park his car and get in mine. We'd have lunch together...once I picked up the oranges. As we proceeded down Osos Street toward the depot, I noticed the time to be 11:00 and in the rearview mirror a city police car following. This didn't concern me until I came out of the express office with my oranges and found the officer talking to Bill. I asked Bill what was up. He didn't know. My attempt for an explanation was unproductive. The officer insisted we follow him to the police station.

At the station we were left in a basement room with instruction to wait there. Although perplexed, we had no cause for apprehension. Yet.... We waited...and we waited. Minutes turned into hours...many hours...in all, five hours.

Finally around 4:30 pm in stormed one C.C. Canny. He was a navy intelligence officer operating in the area. He was not unfamiliar to me. We had met through the Japanese American Citizen League and its activities. On seeing me his first words were, "Pat, what the hell is the matter with you? Don't you know my time is valuable?" I retorted, "So is my time! What is the hell matter with you? Bill and I have been waiting here for five hours with absolutely no idea why!" With exaggerated deliberate motion he pointed to a poster on the wall, to the curfew regulations. Sarcastically he snarled, "Can't you read? Don't you know what those regulations say? You're outside the curfew limit!"

I tried to explain, "Yeah, I'm aware I'm outside the five mile limit...but it doesn't make good sense to go all the way to Santa Maria, some 50 miles away, to get a permit from the WCCA (Wartime Civilian Control Authority) office to travel 15 miles to San Luis to do all those things necessary to being evacuated. If you're going to interpret the curfew so literally...so inflexibly... okay, let me go home...I'll have everyone come to me, rather than me going to them."

What came next completely threw me.

"Pat, you Japs haven't ever done one thing for me all my life...Now why should I do this for you?" "You dirty bastard..."I hissed softly as I bit my tongue in utter disgust and anger.

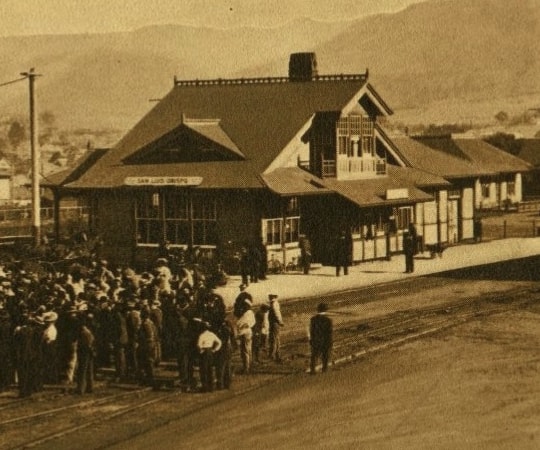

It was near 6 o'clock when Canny left Bill and me at the county jail. At the time the jail was in temporary quarters squeezed into the old records building on the corner of Palm and Osos, while the new courthouse was under construction. The cell was small, dingy, ill-lit, and smelly. On entering the cell, I nearly kicked over a can brimming with the urine of former occupants. There were two bunks stacked one above the other, and no chairs. One could not sit on the bunks without hitting his head. We had not eaten since breakfast. Supper in jail had been served at 4:30. Were it not for a friendly warden who went out and got us some hamburgers we would have had hunger to go with all of our other miseries.

All this had happened on Friday. Next day was Saturday. At 9:00 AM, Canny came by to take us before the U.S. Commissioner. The Commissioner was Richard Harris, who was well known and respected by everyone, including myself. While recognition of the commissioner afforded some reassurance, this whole matter was a totally new experience.

With the preliminary routine questions out of the way, it came down to, "How do you plead...Guilty or not guilty?" "Not guilty!" My response was immediate and instinctive.

To my surprise the answer caused the Commissioner an Canny to leave the room for what seemed an inordinately long time. Upon returning the Commissioner hesitatingly began a recitation of implications of my position, little of which I understood. Obviously, he and I both were having difficulty with the situation.

The last thing I wanted was to be involved in a messy problem. So, I turned to the Commissioner, "Mr. Harris, I've know you for some time, and I'm confident you'll not advise me badly...What do you suggest I do?" The Commissioner seemed relieved as he said, "It would be easier all around if you would plead guilty."...I followed his suggestion. The bail for my release was set for 1000 dollars.

It was near noon when they got us back to jail. One phone call was allowed us, which I utilized to call Mr. Ernest Vollmer, only to fail to make connections. My next bet was Pete Bachino, an insurance broker, who had been a stalwart friend of the Japanese.

My luck held this time. "Pete, I need your help...I'll give you the details later, but right now I'm in jail for curfew violation'I need to be bailed our...The amount is $1000...Please do what you can for me...and incidentally Bill Kuroda is in the same predicament."

Mr. Bachino did not get back to me for what seemed an eternity. While the delay was disconcerting, it was unavoidable, as I was to learn later.

Immediately following my call, Mr. Bachino had hurried to the bank. But it was now past noon, the bank's closing time on Saturdays. As he pondered his dilemma he remembered that Mr. Charles Kaetzel, an attorney, had his office right above the bank, and that he was acquainted with the Naganos. So he wasted no time conferring with Mr. Kaetzel.

Mr. Kaetzel advised Mr. Bachino against cash bail, since it could be too easily forfeited. Property bond would be safer. They agreed Mr. Charles Serrano would be a good choice to ask to put up the bond. He was well established, widely respected, and he knew the Naganos. Accordingly, Mr. Bachino approached Mr. Serrano, who graciously agreed. Thanks to Messr. Pete Gachino, Charles Kaetzel, and Charles Serrano, their faith in me and goodwill, I headed for Morro Bay to make the most of my last few days in the county.

Curfew leaves one with long nights to contemplate. Notwithstanding all the supportive friends I could not help feeling unjustly victimized by events beyond my control. Here I am, doing all I can to be a good citizen, yet being forced to be apart from my family. And solitude allows one full reign of his imagination. It led me to conclude there was one person who could help me, the very on who issued the order, General DeWitt. If only he knew, he might help. I would telephone him first thing in the morning.

Next morning came none too soon. Yet I decided to wait until 9 o'clock, which seemed a more reasonable time to call such a preeminent person. At nine, not a minute later, I placed the call, person to person. I had no idea what number to call, but the operator was very helpful. Finally, I did get through.

A voice came back, "This is Colonel so-and-so, adjutant to the General...What can I do for you?"

"I need to speak to General DeWitt."

"He's in conference at the moment...perhaps I can help."

"Thanks, no. Please have the General call me back when he is free." And I lift my name and number.

Half an hour later a call came back, "This is General DeWitt..What is it that you want to talk to me about?"

"Thank you, General, for returning my call. My name is Pat Nagano, and..." I proceeded to relate the bist I could my situation, concluding with a request to be allowed to join the family in Reedley.

"Young man, this is no matter to be handles by phone?"

"Well, General, I'm desperate...What should I do?...How do I go about it?"

"First you go to your prescribed assembly center. From there write me stating your case. And be sure it is in triplicate:"

"Thank you, sir..."I did not finish my thought which would have been, "Thank you for nothing..."I may not be very sophisticated...but I can recognize a brush off."

Thus, on the designated date, with resignation of going to Tulare Assembly Center, I reported to Arroyo Grande High School to register and receive the required medical shots. The process was quite routine and uneventful. At its conclusion I was sitting there lost in thought about the vagaries of life, when Miss Starkey came by.

She had been a missionary and had spent considerable time in the orient, much of it in China and Japan. The government, utilizing her background, had her assisting in the evacuation process. We had met before, and on recognizing me, asked. "Pat, you seem so forlorn...What's the matter?"

"Oh, Miss Starkey...the inequity of it all...my family is in Reedley...I stayed behind to do as much as I could for my family, and for my country...and here I am, forced to go to Tulare.

After commiserating with me she stood up saying, "Pat, you sty right here...Don't move until I get back." With that she disappeared, but was back in no time with a slip of paper.

"This is a travel permit...it will get you to Reedley...Don't ask any questions...Now, go."

"Miss Starkey, I can't thank you enough... I can't believe you could do this for me...incidentally there are others in the same boat."

"Who are they? Give me their names."

"Bill Kuroda and Karl Taku."

While she was gone, I sought out Bill and Karl to tell them what was happening. They, too, got their permits to join their families.

I took off straight for Reedley, hanging on to the unforgettable impression. Why is it that someone like Miss Starkey would do for me what someone with General DeWitt's capacity would not do.

There was much rejoicing in Reedley. The days that followed were some of my most pleasant, carefree ones. No farm responsibilities. No curfew. It was May. The weather, the countryside, everything was just beautiful. What a nice place to weather the war, I thought. Our spirits were further lifted with dad being released from interment and being able to join us.

All this, however, was no to be for long. As the war intensified and military setbacks mounted, so did the chorus of antagonism against us. The "free" zone, which had been east of Highway 99, was redefined to east of the Sierras.

Faced with another unasked for move, we submitted to forcible evacuation. In August we were taken by train to Poston Relocation Center, located in an Indian reservation along the Colorado River, some 0 miles south of Parker, Arizona.

Live in a relocation center was a new experience, quite unlike anything we had been accustomed to. It was totally communal. Each family had one room, shared wash room facilities, and ate in a common mess hall. Work was voluntary. Pay was $16 a month if classified professional, $14 a month if skilled, and $12 a month if non-skilled. Purportedly all physical necessities were provided. Life was easy and for a while even enjoyable. But soon things became tiresome.

There was little privacy. The system allowed no individuality. It stifled initiative. Much like communism, I remember musing.

Although the situation was temporary, presumably for the duration of the way, marking time in camp was not an attractive option, particularly for the young. Anxious to get on with their lives they began to leave for all parts of the country, the Mountain States, the Midwest, the East. Resettlement was encouraged by the government. It provided assistance, as did many private organizations.

Naganos, too, would soon scatter. I was the first to leave, seizing an opportunity presented by an army recruiting team looking for volunteers for intelligence service. It was November. To go from hot Arizona to cold Minnesota was a drastic change, but no more so than other aspects of my life.

My sister, Nellie, was next. She headed for Philadelphia to a job with War Relocation Authority. She would stay there for the duration.

George, the youngest, finished high school in Poston and enrolled at William Jewell College, located in Liberty, Missouri. After a year, without waiting to be drafted, he too volunteered for the Army Military Intelligence Service.

Mom and Dad were the last to leave Poston. Their resettlement required a firm employment offer before hand. They were able to resettle in Minneapolis, which was propitious in that they would already have some member of the family nearby

It was propitious for me, too. By then I had met and married Ann, and our first child Karen, would be born at Fort Snelling Hospital located between Minneapolis and St. Paul. Since I was overseas at the time it was great comfort to me to have some member of the family nearby.

VE Day, May 8, 1945 found me in Rheims, France, at General Eisenhower's forward headquarters. It was my good fortune to witness the arrival of Germany's surrender team. VJ Day followed in August of the same year. I had just returned from Europe and was on furlough enjoying precious moments with Ann and our new baby daughter.

How quickly one's fortune can change. Here I was facing imminent reassignment to the Pacific once the furlough was over, all of a sudden I'm looking at an unexpected discharge. Of course, it would take some time for my records to catch up with me, but my stint in Europe gave me enough points to get me over the hump. Now it was just a matter of time.

The army eventually got around to sending me to Fort McArthur in San Pedro for discharge. Who should be there also getting his discharge but my brother, Bill. The date was December 15, 1945, exactly three years and one month since I volunteered from Poston.

Bill and came home together. Dad and Mom were already there. They had returned by car in September, as soon as they were allowed to do so. Ann and Karen had followed several weeks later, traveling by train, which everyone had agreed would be safer and easier for the mother and the baby. Once again we were all together as a family, and best of all, in our own home.

Everything was intact and ship shape, just as we had left it some three and a half yeas ago. All the trust we had placed in friends, in particular in Vollmers, who had managed the property, and our dear and helpful neighbor the Brughellis, served us well, as did our faith in our country and her sense of justice. The Naganos were able to resume their lives in Morro Bay much as before.

World War II, which had disrupted everybody's existence, seemed in some respects to have lasted a lifetime, when in reality, it was successfully concluded in far shorter time than even the most optimistic anticipated. Of the many unforgettable experiences squeezed into this brief time frame, the one I cherish the most is the sense of belonging and the exhilaration of being a part of a nation totally united in a common cause.

In retrospect, in what might have been a very mundane life, the war and evacuation was a bitter sweet interlude.

Read this original story on the Historical Morro Bay website at http://www.oldmorrobay.com/nagano.html

Return to QR Index